Damac : Hussain Sajwani, chairman of Dubai’s largest private sector property developer, is on a mission to persuade the world that he – like his home town – is back.

Damac, the company he founded in 2002, was at the heart of the city’s real estate bubble that made millionaires of some and destroyed the life savings of others when it burst in the summer of 2008.

damac

But Dubai’s property prices have surged by as much as 50 per cent over the past year after the emirate emerged as the regional haven for investors fleeing either regional unrest or the taxman back home.

Over conversations in the opulent majlis in Damac’s headquarters, Mr Sajwani builds the case for a new construction boom over coffee served in Damac-branded espresso cups. The 62-year-old chairman believes the construction lull of the past four years has created a shortage of housing stock in the city’s more sought-after areas, such as the thriving district around the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building.

“The market in the next three years will be very strong, especially in the high end,” he says in his low, gravelly voice, rejecting concerns that the sector is in danger of overheating once again.

Very much the image of a Dubai tycoon, Mr Sajwani fires off phone calls to underlings for updates on the latest market capitalisation of his businesses as he outlines the financial growth in his portfolio of diversified regional companies. He is also not a stranger to the company’s motto, “live the luxury”; his four children’s favourite day out is lunch at Zuma, the high-end Japanese eatery.

But his business empire grew from modest beginnings.

Born into a middle-class Dubai family with Omani roots, Mr Sajwani’s father worked long hours at his store in Deira souk while his mother hawked goods to local ladies from their home. “I used to listen to all the stories, the successes and the failures, the issues that an entrepreneur faces in life,” he says of his childhood, when Dubai was still a minor trading post.

He sold timeshare apartments in the United Arab Emirates even before he left the University of Washington in the US and, after moving back home, he quickly left his public sector job to branch out into business.

Using his timeshare profits, Mr Sajwani set up a catering company in Abu Dhabi. He expanded across the Gulf, building one of the largest catering companies in the region, supplying the US military through both Iraq wars, as well as during the conflicts in Bosnia, Somalia and Afghanistan. He also supplied multinationals working in the oil and gas industries, from Bechtel and Fluor Daniel to Chiyoda and JGC.

He piled his profits into the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, including internet service provider Juno and mail.com. Some have claimed he doubled up into local property to recoup massive losses, but Mr Sajwani says he came out of the internet crash “about even”.

Out of the ashes of the dotcom debacle, Dubai in 2001 lit the touch paper of its property explosion by opening real estate ownership to foreigners in specific freehold zones. “I saw a major opportunity, a change in the landscape,” he says.

Selling prime land at a loss – his “bravest decision” – allowed Mr Sajwani to buy two plots in a barren area that a decade later is now one of the city’s most popular residential districts, Dubai’s skyscraper-packed Marina.

With the property frenzy fuelled by cheap credit and rocketing oil prices, Damac launched dozens of projects in Dubai and across the rest of the Middle East as down payments flooded in. Mr Sajwani was renowned for his marketing gimmicks, such as a luxury car or the chance to win a private island with each sale.

But by 2006, property deliveries were already behind schedule, an issue he blames on late handovers from the city’s master planners. And then the speculative bubble burst in 2008 as the global economy screeched to a halt. “I was on holiday in London and saw prices go down, so I spoke to the management team and put in an action plan,” he says. “We knew the storm was coming heavy and strong, so we cut our overheads to the bone.”

Damac slashed staff and, using $275m of funds held in escrow, renegotiated with contractors as it moved customers from cancelled towers into the buildings that would be completed.

For several years, the developer faced an avalanche of legal cases. “There was a fire and everyone wanted to leave the room,” he says.

Damac has won 90 per cent of these claims, Mr Sajwani says. And while the company was notorious for dragging its feet in the early days of the crisis, Damac has more recently developed a reputation for settling promptly with aggrieved customers.

As construction restarted, Damac’s cranes often seemed to be the only operational ones across Dubai’s skyline as other developers went to the wall.

Rumours swirled that the company – one of the few privately owned developers to survive the onslaught – was receiving secret bailouts from the Dubai government or Iranian investors. He rejects the claims “100 per cent”.

“Lots of people make rumours,” he says, the only time his calm demeanour breaks into irritation as he asks for the source of this gossip. “They aren’t happy when they see competence in the private sector.”

Other controversies have hit Damac’s owner, including a criminal conviction for a land deal with the ousted regime of President Hosni Mubarak in the wake of Egypt’s 2011 revolution.

Mr Sajwani, along with other overseas investors, has settled his Egyptian disputes after two years of negotiations, saying he is now looking forward to restarting projects in the troubled state.

damac

Amid its renewed expansion plans, Damac is also eyeing a London stock market listing. Mr Sajwani won’t be drawn on details, saying “we haven’t made a decision yet”.

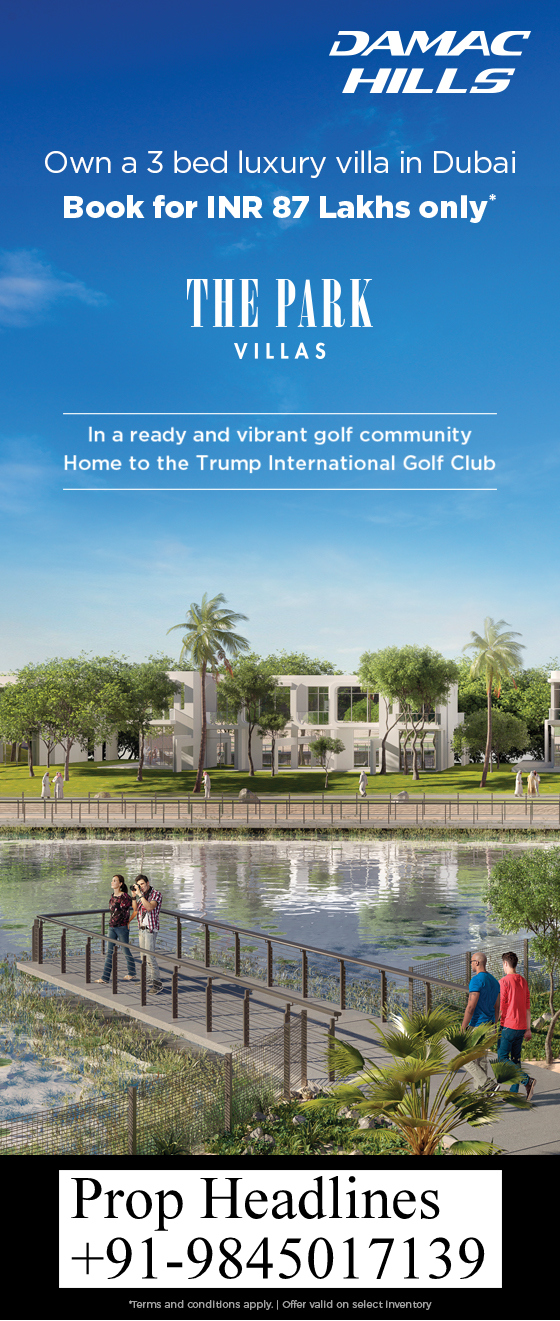

As a privately held company, Damac does not release financial data. But it has delivered 8,000 units in 37 buildings, with another 65 three-quarters complete. It now hopes to offer global investors exposure to projects in the rebounding market of Dubai and other countries in the region, such as Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. Mr Sajwani is pushing ahead with Hollywood-themed villas in partnership with Paramount, a UAE golf development with Donald Trump, and apartments outfitted by Italian designer Fendi.

But Mr Sajwani says buyers are now protected by stronger property regulation and more responsible developers. “We learn from mistakes and learn from our history,” he says. “Today we are much stronger management-wise, and we will only carry projects the market can absorb.”

For Updated Residential news Log on to http://propheadlines.com